Zach Winn | MIT News Office

July 11, 2019

Genevieve Barnard Oni’s iPhone lights up with the same notifications dozens of times each day — but they aren’t from a popular Instagram account or an overactive group chat. Instead, the notifications signal every time a patient is treated at MDaaS Global’s health clinic in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Last month Barnard Oni MBA ’19, who co-founded the company with her husband, Oluwasoga (Soga) Oni SM ’16, as well as Joe McCord SM ’15 and Opeyemi Ologun, received 750 such notifications. If all goes according to plan, that number is about to multiply.

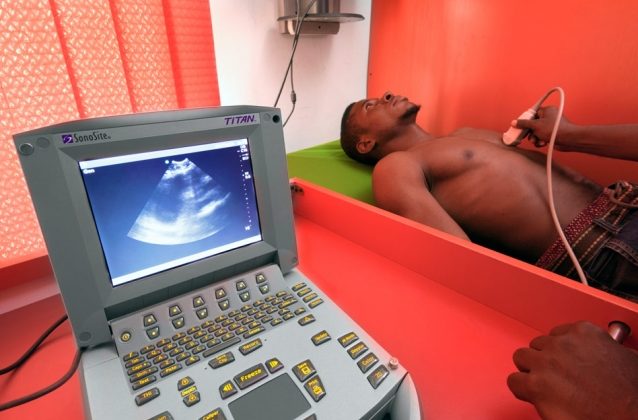

Operating outside of the wealthier, well-resourced city center, the company’s clinic offers affordable diagnostic services, including ultrasounds, X-rays, malaria tests, and other lab services, that were previously inaccessible to many families in the area.

MDaaS has accomplished this by building a supply chain that gets refurbished medical equipment into the African communities that need them most, and by leveraging technology to streamline clinic operations.

By partnering with dozens of nearby hospitals and clinics to get patient referrals, the MDaaS clinic has diagnosed more than 10,000 patients since opening less than two years ago. Now, fresh off a $1 million funding round, the company is planning to export its model to other areas of Nigeria and West Africa, with the goal of operating 100 diagnostic centers in the next five years.

“We’re trying to build four diagnostic centers [by early next year] and show that the new centers will have the same trajectory as our first,” Soga says. “After we’ve proven that, we can start building for scale, building maybe two or three centers a month all over Africa, the idea being we know exactly how things will go when you build them.”

A desperate situation

Soga’s father runs a private medical practice in Ikare-Akoko, Nigeria. Like many doctors in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa, he has long struggled to get reliable medical equipment at affordable prices. Negotiating to purchase used equipment from Europe or China requires expertise in the global equipment marketplace and also comes with risks, as most secondhand equipment lacks warranties and operating manuals.

Genevieve, on the other hand, worked on public health initiatives in Malawi, Ghana, and Uganda before coming to MIT. During those experiences, she realized how useless donated medical equipment is without technicians trained to set up and maintain them, and without access to spare parts.

“Countless times I saw rooms full of equipment that had never been set up or equipment that had been used for a few months before breaking down, with no hope of repair,” she says.

A common goal

Soga entered MIT’s system design and management graduate program in 2014 and met Genevieve later that year. The two quickly realized they shared a passion for improving health care in Africa. For their second date, Soga invited Genevieve to his development ventures class, where he pitched a rough idea for providing rural doctors like his father with high-quality, refurbished medical equipment and ongoing service support.

MIT offered Soga and Genevieve seed funding to further pursue the idea through the Legatum Center, the PKG Center, MIT IDEAS, and the Africa Business Club.

McCord joined the team in the summer of 2016, and the co-founders were able to secure a partnership with Coast 2 Coast Medical in Massachusetts to begin buying refurbished medical equipment in bulk.

But when they began selling the equipment in Nigeria, they realized their biggest customers were from hospitals and clinics in big cities that predominantly served high-income patients. These facilities already had access to many of the machines MDaaS was selling, but found they could save money through the startup.

The founders faced a dilemma: They weren’t serving the people that needed them most, the low-income communities they’d dreamed of helping since their time in Africa, and yet, by the summer of 2017, the business was profitable — a difficult milestone for startups anywhere, let alone one in Nigeria. They tried different financing options to get their equipment to poorer clinics, including offering to lease or rent out the equipment, but clinics in rural and low-income areas still struggled to achieve the patient volumes necessary to make it work.

“We weren’t reaching this really large market, the 130 million patients that live outside of the largest urban areas that have the biggest issues accessing medical equipment,” Soga says. “The market of high-end hospitals wasn’t exciting for us. … We’d be stuck in big cities, serving high-end clientele. That wasn’t what drove us.”

Upending their business model, they decided to take on new costs and open their own diagnostic center in a low-income community in southwestern Nigeria. The people in this community had limited access to the high-quality diagnostic services enabled by the company’s machines. By centralizing diagnostic services, the founders could aggregate patient demand across dozens of hospitals and clinics, helping them keep prices low and scale faster than if they just sold equipment. This approach would also give the founders a chance to work directly with the patients they were trying to help.

Even as they faced bigger challenges and risks associated with the new model, they never planned to stop at one clinic.

“We had to make the change,” Soga says. “We just kept following our north star, which is to improve health care outcomes. Anybody can build one clinic, but it gets really interesting when you’re building 20, 30, 40 clinics across the continent.”

The MDaaS clinic has been up and running since November 2017. It features a digital X-ray machine, an electrocardiogram (ECG), an electroencephalogram (EEG), an ultrasound, and a full suite lab. For most tests, in-house physicians interpret the results. For others, results are sent to specialized clinicians in big cities.

Today, MDaaS gets patient referrals from more than 60 hospitals and clinics in the region in addition to welcoming walk-ins and partnering with insurance companies. About 70 percent of the people MDaaS treats are women and children.

The founders say they broke even on their operations in just five months and have been operating profitably ever since, proving the need for their services in the area. In fact, the number of patients seen per day at the center has grown by a factor of five since January 2018.

Their dream of operating 100 diagnostic centers will begin by building a few more in Nigeria before they expand to nearby countries, including Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire, possibly as early as next year.

“Right now, we want to test replicating what we have and learn how to manage multiple facilities at once,” Soga says.

As for Genevieve’s mounting phone notifications, she remains thrilled to get constant reminders of the impact the co-founders’ hard work is having. Still, with the ultimate goal of transforming care across sub-Saharan Africa, she admits she’ll have to turn them off at some point soon.

“We’re trying to get to the point where it’s almost a diagnostic center in a box,” she says. “We can provide everything you’d need to go from zero patients to seeing 1,000 or 2,000 a month. We’re also getting so much data and information about the people we’re seeing, so we know the diseases they’re coming in for and the type of diagnostics they need. This information will become increasingly important as we look to build health care solutions for hundreds of thousands of patients instead of tens of thousands.”

Reprinted with permission of MIT News.

Image courtesy of MDaaS Global