SEE STORY ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED AT WBUR.ORG

As frequent collaborators on documentary film projects on and off over the last 10 years, Sharon Shattuck and Ian Cheney kept observing one common fact: It’s harder to find women and people of color to feature in their science-based films. In an interview with the co-directors by phone, Shattuck says that’s because women make up less than one-third of all working scientists, “and obviously there are even fewer women of color. It’s pretty striking.”

Yet the observable lack of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) hardly tells the whole story. Zoom in on women’s qualitative experience, one in which sexual harassment affects 50% of women faculty and staff in academia and other insidious forms of discrimination are nearly inescapable, and a dubious reality sets in. Women might find a coronavirus vaccine or a cancer cure, but not without enduring systemic gender bias, with barriers compounded for women of color.

With that in mind, the co-directors seized the chance to put the story behind the groundbreaking 1999 MIT Report to film. “A Study on the Status of Women Faculty in Science at MIT” documented the flat line percentage of women faculty over one decade, gave explicit reasons for women’s attrition, and offered recommendations like equal pay and on-campus child care. (Amy Brand, the director of MIT Press, approached Cheney with the idea and is an executive producer on the film.) Through three women scientists at different stages in their careers, including biologist Nancy Hopkins who spearheaded MIT’s report, the new documentary “Picture a Scientist” combines poignant, firsthand recollections of sexist and racist treatment with indisputable current data. Time has improved the situation somewhat, but not enough, the film asserts.

While Hopkins says she was “tremendously impressed” by the film and “profoundly moved in a way I hadn’t expected,” she remains frustrated that women in younger generations are still facing difficulties that she helped name, quantify, and change at MIT. The initial report had a ripple effect; Hopkins fielded hundreds of requests to present its findings to help guide other institutions. In the film, she says she became “a radical activist against my wishes” and talks about devoting countless hours to advocacy, while never wavering on her first love of cancer research. All of that leaves her impatient for justice today. When considering the film’s potential impact, she says, “You hear people talking endlessly about diversity. What is the problem? Let’s do it.”

So urgent is the film’s overall message, Cheney says, “Sharon and I might have made this film together at some point anyway because it was a film that needed to be made for all the reasons that hopefully become evident.”

Brought to sharper focus amidst global protests against racism, “Picture a Scientist” concretely illustrates how prejudice functions. Using an iceberg as an extended metaphor, the film starts at the visible portion, in Antarctica, where Boston University graduate student Jane Willenbring experienced traumatizing sexual harassment in 1999. (Shattuck expertly animates imagery throughout the film, including the iceberg and inclusion of women scientists in vintage textbooks to shake up the default image that comes to mind.)

Now tenured faculty at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, Willenbring describes how Boston University professor David Marchant bullied her with slurs (“sl-t,” “b—h,” “c–t”), pushed her down a steep hill multiple times, and blew ash with shards of glass into her eyes. (Science, WBUR and other outlets reported on this and additional complaints against Marchant.) Willenbring knew Marchant’s behavior was wrong at the time but says she needed to wait until she had the security of tenure before filing a Title IX complaint. Later in the film, Willenbring meets up with Adam Lewis, who witnessed the incidences and substantiated her complaint. He admits he didn’t realize how much the mistreatment had hurt his friend.

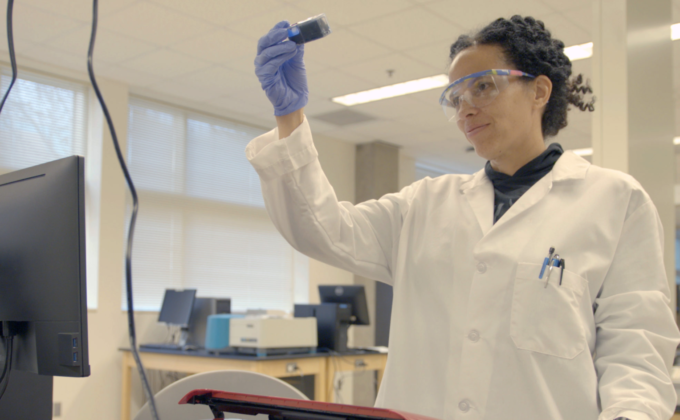

Jane Willenbring in a still from the documentary “Picture a Scientist.” (Courtesy)

If Willenbring’s experience is observable from the surface, the type that codes of conduct are designed to prevent, then the bulk of what happens to women scientists makes up the hidden but still obstructive iceberg. Whether treated like a technician or mistaken for a custodian while on faculty, ignored in meetings, sent inappropriate emails, or denied earned credit or lab space, the microaggressions spelled out by Hopkins, who has experienced discriminations from the 1970s onward, or by chemist (and Twitter influencer) Raychelle Burks, still battling them day to day, add up.

“You spend all this time trying to craft an approach,” says Burks in the film. That’s time spent not doing research or not writing grants. Not only do scientists in the privileged majority not have to navigate oppressive systems, but she says that for them, “it doesn’t even register.” Wearing fun superhero T-shirts in much of the film (with phrases like “Wakanda Forever” from “Black Panther,” and the Wonder Woman emblem), in a later scene, Burks – illustrating her point — dresses more formally to present a session on code-switching to her colleagues at a science conference. She points out the stress of being both invisible and hyper visible, yet doesn’t want to “chase this mythology of what a scientist is.”

At around age 50, Hopkins recounts in the film how she found herself at a crossroads. Either retire or fight. She decided to start discreetly measuring lab space of all tenured faculty (15 women versus 194 men in six departments). At first, no higher-ups would even look at her disproportionate results. When she finally approached another woman faculty member with the data, she recalls worrying over whether her colleague would think she wasn’t a good enough scientist, and that’s why she wasn’t getting the lab space she needed.

In hindsight, after seeing the film, Hopkins says, “We believed so much in meritocracy. That you cannot keep merit down. False.” She cites the 2006 resignation of Larry Summers, then president of Harvard, precipitated by his writing all women off as incapable of performing science at the level of men.

“Really, that’s what was behind this fear,” says Hopkins. For women and Black people, the fear is that “your whole group is not good enough. Women were so terrified of being lumped into that horrible prejudice.”

When speaking by phone about the film, both Hopkins and Willenbring mention climate change as another way to think about the realities women in science face. Hopkins says that maybe 25 years ago, people didn’t understand unconscious bias. That’s no longer the case, she says. “We have to accept the fact this kind of prejudice exists. It’s like denying climate change, which is ridiculous. This is a reality.”

Making this film has personal significance to Shattuck. She studied forest ecology and botany as an undergraduate. While she never felt she shouldn’t be a scientist, she says, “I definitely know the feeling, the feeling as though you didn’t get a job because you were a woman, probably, but not ever being able to prove it.” That suspicion of an unseen undercurrent can make women, or any group experiencing prejudice, blame themselves and turn away from something in which they excel. One of the main ways to change that is to talk about it, says Shattuck.

Willenbring is no stranger to sharing her story of harassment as a means to create environments where women scientists — all scientists — can thrive. “One of the most powerful ways to get people to change behavior around racism and sexism is hearing personal stories about how it harmed them. You can’t replicate that in yearly sexual harassment training,” she says in a phone interview. She’d like to see “Picture a Scientist” become part of science department training. “I think it has a chance of being a powerful change-maker,” she says.

Shattuck also hopes that the documentary will offer a roadmap for people who want to make change at their institutions. Because to solve science’s most daunting questions, every voice is needed. “Coming from the same perspective, like economic class or region of the country, we’re losing out on other perspectives and other ideas,” says Shattuck. “It’s really important to try to level the playing field so white men don’t have all the advantages.”

CLICK HERE to learn more about MIT Innovation Initiative’s Inclusive Innovation Program.