READ STORY ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED AT MITSLOAN.MIT.EDU

by Fiona Murray and Ray Reagans | Sep 22, 2021

U.S. business schools do not reflect the face of the U.S. population. Traditionally, their students are predominantly white and male. According to accreditation organization AACSB International, 8% of MBA students at its member organizations in the U.S. are Black (although Black people make up 13% of the U.S. population), 9% are Latino (19% of the population), and only 41% globally are women.

These numbers are even lower in corporate executive ranks. Black people hold only 3% of executive or senior-level roles at U.S. companies with at least 100 employees, according to U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission data. And women hold only 21% of C-suite level roles in the U.S.

Recent events — including the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, inequities in health highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and rising violence against various ethnic groups — spotlight this lack of diversity, equity and inclusion. Academia and business can do better.

The MIT Sloan School of Management recognizes the need to improve DEI among its students, faculty, and staff. Like many schools and companies, we have spent the past several years designing a strategy to do so. What are we doing that’s different from the diversity efforts that have struggled or sputtered out in many organizations? By building upon decades of MIT Sloan research in organizational design and system dynamics, we’ve developed a holistic approach, one that we believe has a better chance of improving DEI in a more lasting way than traditional methods that have frequently been applied. At the heart of the strategy is a strong belief, grounded in our academic research and lived experience, that systemic problems require systemic solutions. We hope that a more systemic approach will not only yield enduring change at MIT Sloan, but also provide lessons that can be adopted at organizations around the world.

Defining the problem

Our sharpened focus on DEI began in 2019 when our student senate, supported by a committed group of alumni, shared its disappointment in MIT Sloan’s slowness to increase diversity across our population of students, faculty, and staff. That year, the graduating MBA class at MIT Sloan, which includes students in our Leaders for Global Operations program, was 8% Black, 11% Latinx (both as a percentage of U.S. citizens and permanent residents) and 42% female. The senate requested the creation of a senior (dean-level) position focused on DEI to signal the school’s commitment to DEI and make that commitment more visible.

At the heart of the strategy is a strong belief … that systemic problems require systemic solutions.

In response, our dean,David Schmittlein, formed a task force of faculty, staff, students, and alumni who, after a series of meetings, interviews, and deep dives into the data and experience of our community, published their findings in February 2020. The group recommended ways to increase diversity and build a more inclusive climate both inside and outside the classroom. In April 2020, in recognition of the scope of the change needed, Dean Schmittlein tapped the two of us as longtime MIT faculty members to be Associate Dean for Innovation and Inclusion and Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, respectively, with a commitment to bring in an Assistant Dean for DEI with professional experience in leading change in a range of organizations. We were joined by Bryan Thomas, Jr., in August 2021.

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic surged across the country, highlighting health disparities among racial and socioeconomic groups. Then came the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020, which further energized the already-growing Black Lives Matter movement and led to a wave of outrage and protest worldwide. At MIT Sloan, the Black Business Students Association said Black students felt unsupported by our community during these troubling times. The group organized a town hall meeting where administrators, faculty, staff, and students had a frank discussion of the situation. The honesty with which students shared their suffering added a new and very personal urgency to our mission.

We assumed our new roles well aware of research that has found that traditional DEI approaches don’t work. We knew we wanted to do things differently. As we reviewed the task force recommendations, we drew on MIT research to devise an approach that would begin with individuals, move to groups, and ultimately build a constructive culture of conscious inclusion across the entire organization.

A systems approach

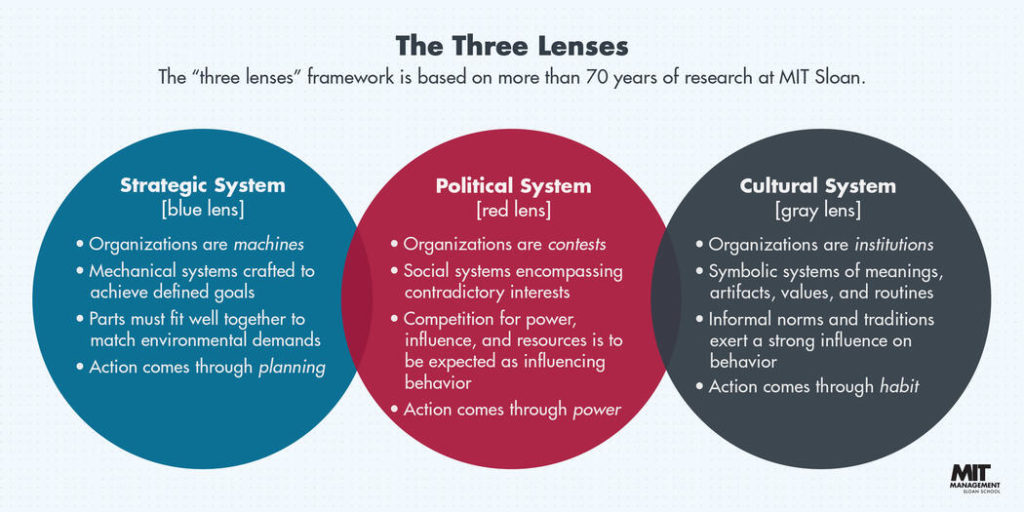

As MIT’s school of management, MIT Sloan is predisposed to taking an organizational perspective. The school developed a substantial body of work on organizational processes over the years, based on coursework, seminars, and research. Formally published in the 1996 book “Managing for the Future: Organizational Behavior and Processes” (whose co-authors include MIT Sloan professorsDeborah Ancona andThomas Kochan and professor emeritusJohn Van Maanen) and taught as part of the core curriculum, it uses a framework of three perspectives, or lenses, through which organizations can be viewed: strategic, political, and cultural. Each lens examines an organization in a different way, looking at how decisions are made and actions are taken. Together, the three lenses encompass the entire organizational system and how it functions.

Viewed through a strategic lens, organizations function as rational systems, designed and constructed to achieve specific, well-defined goals. Through a political lens, organizations are social systems in which individuals and groups often compete for resources and drive change via networks of influence. And through a cultural lens, organizations are shaped by underlying beliefs and behaviors that are so routine and taken for granted, we rarely notice them in our daily lives.

We identified strategic issues that impact DEI at MIT Sloan and are making changes to address them. For example, we are taking steps to further diversify the talent pipeline from which we draw staff, faculty, and students. We are adjusting our interview processes, changing questions and how we ask them in order to be more balanced and reduce opportunities for biased decision making. We are ensuring that we ask all candidates the same interview questions in the same way. This approach draws on Fiona’s research that found evidence that women pitching their ideas are evaluated differently from men, even when presenting the same ideas. The research found that potential investors had very different ratings for the competence and investment worthiness of men and women. This is closely linked to to other research showing that the kinds of questions venture capitalists asked male startup founders seeking funding were different from the questions they asked female founders. VCs typically asked men to explain why their startups would succeed, but tended to ask women why their businesses might fail. The very questions they chose to ask candidates reflected an assumption that men are risk-takers while women are risk-averse, and translated into less funding for women-led startups.

One aspect of the organization as seen through the political lens is the value of networks. We are addressing the school’s traditional reliance on our existing networks to recruit staff, faculty, and students, an approach that inherently reflects our white, male population. To change that, we’ve hired specialized recruiting firms to tap into broader, more diverse networks when hiring staff.

Our ultimate goal is to permanently transform how culture — the third lens — positively affects DEI. If the culture does not change, any changes made in the strategic and political arenas are not likely to last.

Toward an inclusive culture

There are two levels of culture: individual and institutional. Individually, people act based on their own internal contexts and life experiences. We all see the world through our own unique pair of glasses, which explains why different people can perceive the same situation very differently. Yet organizations often fail to recognize the differences in individual perspectives. Students admitted to MIT, for example, typically come from the top of their classes. During orientation, tradition has been to “re-orient” them to a much more academically competitive environment. “Look around you,” they have been told in introductory sessions. “You’re surrounded by people who are all smarter than you are.” While some students may hear that statement as an energizing challenge, others may find it insulting or intimidating. Reframing that moment — instead asking people to look around and recognize that the diversity of talent around them will help them solve harder problems in more creative ways — can help change the culture at an individual level by changing the way we talk about our community.

Institutional culture is based on the organization’s internal context. It is a set of unwritten rules, often casually referred to as “the way we do things here.” Our colleagueEd Schein defines institutional culture as “a pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered or developed in learning to cope with its problems and which have worked well enough to be considered as valid and therefore to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in respect to [its] problems.” These shared assumptions can create DEI barriers that the organization doesn’t even realize are there. As Schein notes: Asking someone about the culture they are in is like trying to “ask the fish what [it] thinks of the water.”

MIT Sloan is trying to identify and eliminate such barriers. We no longer make assumptions about the lived experience of students. For example, we don’t assume that a student with Black skin has lived the African American experience, as they may very well be from another part of the world.

Our reliance on existing networks for hiring was another element of institutional culture. As we have enlisted outside firms to expand our searches, managers have discovered new hiring avenues. When encouraged to rely less on existing networks, one manager initially struggled to find diverse candidates. Eventually, as she tapped into new networks, she saw that qualified diverse people were available and learned how MIT Sloan can recruit them. The experience changed the way she thought about recruiting and hiring. As we hire more diverse staff, we hope to create a ripple effect that helps us attract and retain a more diverse population throughout the institution. It’s an example of needed systemic change: after all, faculty, staff and students may doubt that MIT Sloan is the right fit if they don’t see many people here who look like them. By increasing representation, we can begin a positive cycle that will increase inclusion as well.

Moving beyond unconscious bias

There are other actions we are taking to increase diversity and inclusion at both the individual and institutional levels.

We are teaching people how to be aware of their own unconscious biases and subjective beliefs, and how bias can affect their interactions when working within, or leading, a group. We have introduced training on racial dialogue and cross-cultural communication into our MBA student orientation, and plan to expand such training for everyone at the school. Implicit bias was the theme of our core curriculum across all courses for the 2020-21 academic year. Students were taught about research that demonstrates systemic racism — for example, they learned how redacting names (which can indicate gender or race) changes how managers evaluate resumes. We discussed how such bias can be programmed into algorithms, as well as how to prevent it, or recognize and remove it from existing algorithms.

We are engaging with staff to find more productive ways to talk about race and engage constructively in difficult conversations. The goal is for everyone to feel more comfortable sharing and discussing their viewpoints, even when there is conflict. That’s how we broaden ourselves to more diverse perspectives and learn how to be actively, consciously inclusive, rather than just less biased or simply polite.

We hope these efforts will affect group dynamics at the small group level, and ultimately throughout the entire organization. But training and education does not automatically or permanently change behavior.

Traditional approaches to DEI rely heavily on training — the aim is to change the way people think, under the assumption that will change how they act. Our approach focuses more heavily on action. Rather than thinking our way into a new way of acting, we can act our way into a new way of thinking. The experience of the MIT Sloan hiring manager illustrates how this can work. She thought there were no diverse qualified candidates because she had not found any using her existing networks. Once she used new channels and new ways to find candidates through recruiters focused on diverse populations, she realized that the candidates were there. She now has the experience of finding those people. That action, that experience, has changed her way of thinking.

This experience is also common in corporations, where department managers tend to rely on the same networks of personal connections and universities to fill job openings. For technology jobs, for example, hiring managers often find it challenging to recruit across gender and race because their networks are highly homogeneous. When they recruit at MIT Sloan, we can use our experience to suggest ways to recruit beyond traditional channels.

Even if we succeed in changing individual behaviors (and thoughts), old behaviors are likely to reemerge unless change happens at the system level. In traditional DEI approaches, organizations often set an end goal without changing the means by which they reach the goal. For example, they may aim to increase the percentage of employees from an underrepresented group from 3% to 6%. But they fail to identify and correct the institutional factors that led to the imbalance in representation in the first place. Even if they succeed in reaching the target of 6%, that proportion will tend to fall back down over time. Diverse employees will leave if institutional culture is not inclusive and equitable. This puts organizations on a treadmill of continually trying to recruit diverse employees who stay only a year or two and then leave, at a cost to themselves and to the organization.

Some might not even join in the first place, if they detect a culture that isn’t welcoming. MIT Sloan identifies and recruits a fair number of diverse candidates for our MBA program, but many of them choose to go elsewhere. When we studied the issue, we identified two reasons why: First, MIT Sloan’s existing lack of diversity creates a less-than-welcoming perception in the minds of diverse candidates. Second, the school doesn’t offer financial incentives comparable to other business schools. We are tackling both of those issues today.

Another institutional issue is critical mass. It seems that levels of diversity must hit certain thresholds to have real and lasting impact on an organization. Women need to hold at least three seats on a board of directors before they can substantially change the dynamics of the board. Hence our efforts to increase diverse representation across our entire population of students, faculty, and staff, to create a more welcoming community for future candidates and a more inclusive and less isolating experience for those already here. While there is much work still to be done, the MBA class of 2023 represents some progress; Black and Latinx students now make up 10% and 15% of the student population that are U.S. citizens or permanent residents, respectively, up from the 2019 levels that prompted the student senate to urge greater focus on DEI at the school. The proportion of women in the class is also slightly higher, at 44% percent.

By implementing a wide range of changes grounded in research — some seemingly small, and others large — we are driving systemic change at MIT Sloan. Across the community we are working as individuals to recognize our own personal bias and understand that each individual’s experience is subjective. In teams and groups, we are learning how to talk with each other constructively about unconscious bias. Ultimately, as an entire organization, we will move to conscious inclusion, building a constructive community at the systemwide level.

See more Inclusive Innovation News

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR INCLUSIVE INNOVATION ACTIVITIES |